1930 – The Slide Deepens

A New Year, A False Hope

As 1930 dawned, the initial shock of the 1929 crash had begun to settle. In January, there remained cautious optimism in certain quarters. Many Americans hoped the downturn was a temporary setback. Newspapers printed upbeat forecasts. Political leaders, too, projected stability.

President Herbert Hoover assured the public that “the fundamental business of the country… is on a sound and prosperous basis.” Stocks had stabilized somewhat by early spring, and some economic indicators even ticked upward. But this reprieve was short-lived.

“The market crash of 1929 was a signal flare, not the explosion itself,” explains Dr. Helena Markov, historian at Defined Benefits. “1930 was the year the Great Depression began to root itself in everyday life.”

Economic Erosion Across America

By the middle of 1930, the economic damage that had begun in financial markets was spreading rapidly through the real economy.

Unemployment, which had hovered around 3% before the crash, climbed past 8% by mid-year and was accelerating. Major employers in manufacturing, railroads, and construction laid off workers en masse. With less income, Americans spent less—deepening the recession.

In the agricultural heartland, farmers were crushed by falling crop prices. Wheat prices dropped from $1.03 a bushel in 1929 to as low as 38 cents by late 1930. Farmers, already burdened by debt from the 1920s, couldn’t sell their produce for a profit and began defaulting on loans.

“1930 was the year that pain spread from Wall Street to the wheat fields and factory floors,” says Dr. Leon Briggs, senior fellow at Defined Benefits. “It was no longer a financial panic—it was an economic contagion.”

Hoover’s Voluntarist Approach

President Hoover’s ideology shaped much of the federal response in 1930. A strong believer in limited government and individual enterprise, Hoover resisted direct intervention in the economy.

Instead, he relied on voluntary cooperation between business leaders and civic organizations. He convened summits of industrialists, urging them to maintain wages and production. He also encouraged banks to continue lending.

To Hoover’s credit, he did increase public works spending, directing funds to road building and other infrastructure projects. But these efforts were modest compared to the scale of the unfolding crisis.

Most controversially, in June 1930, Hoover signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act—raising tariffs on over 20,000 imported goods. Intended to protect American industries, it instead provoked retaliatory tariffs from key trade partners like Canada, France, and Germany.

“Smoot-Hawley turned a downturn into a global economic war,” Professor Briggs notes. “International trade collapsed, and U.S. exports fell by nearly 50% in the following year.”

Bank Failures and Credit Constriction

Confidence in the banking system began to deteriorate in 1930. In November, the Bank of United States in New York collapsed, triggering a panic and accelerating a wave of bank failures. Although it was a private bank, the name misled many depositors into thinking it was federally backed.

Throughout the year, over 1,300 banks failed, destroying savings and shrinking credit for businesses. In rural communities, bank failures also meant the collapse of local economies. With no FDIC in place, depositors had no recourse.

“1930 marked the first true erosion of the American financial infrastructure,” Dr. Markov explains. “There was no safety net. Every bank closure felt like the end of the world for that town.”

Dust on the Horizon: Environmental Disaster Looms

While the Dust Bowl is typically associated with the mid-1930s, its roots trace back to 1930. Severe drought struck parts of the Midwest and Southern Plains, compounding the misery of farmers already grappling with debt and low prices.

Without crop rotation or conservation practices, millions of acres had been over-plowed during the boom years, leaving topsoil exposed. As the drought intensified, the first dust storms began to appear—harbingers of the ecological catastrophe to come.

In Kansas, Texas, and Oklahoma, families began abandoning their farms. Those who stayed faced starvation. Breadlines formed even in rural areas.

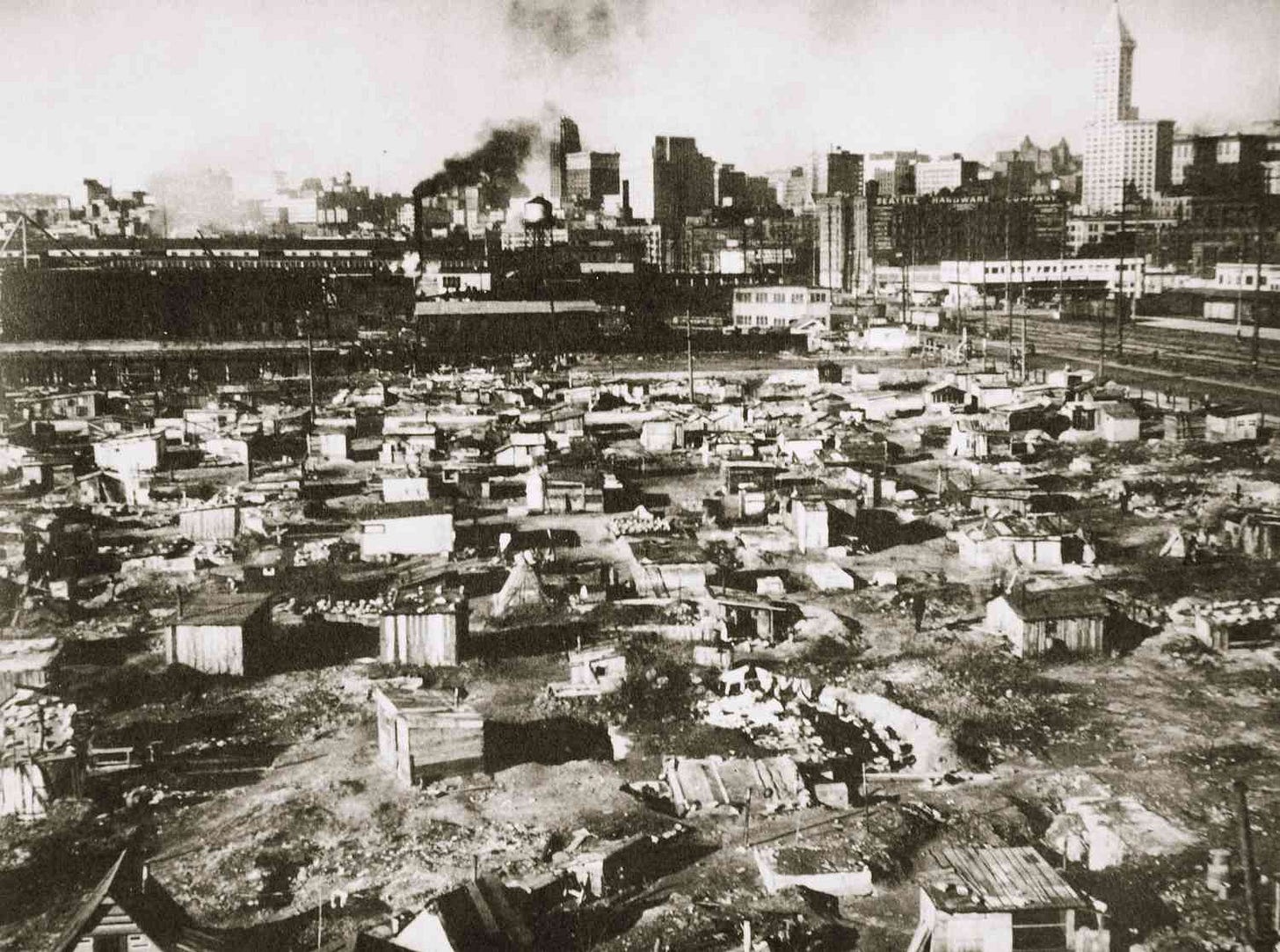

The Rise of Shantytowns – “Hoovervilles”

By the fall of 1930, homelessness had become a national issue. People evicted from homes or farms gathered in makeshift communities—collections of tents, wooden shacks, and tar-paper huts. These “Hoovervilles” sprouted in cities like New York, Chicago, and St. Louis.

Naming them after President Hoover reflected public anger at what was seen as a detached, ineffective response to the crisis.

“Hoovervilles were both a shelter and a protest,” says Briggs. “They were visual indictments of inaction.”

Cultural Response: Songs, Satire, and Survival

Even amid hardship, Americans sought ways to make sense of the chaos. Popular culture began to reflect the grim realities. In 1930, the song Brother, Can You Spare a Dime? wasn’t yet released (it came in 1931), but vaudeville shows and newspaper cartoons began satirizing Wall Street elites and the government’s response.

Literature, especially in the form of short stories and serialized fiction, took a darker turn. Writers began to focus on working-class struggles, the cruelty of evictions, and the hopelessness of joblessness.

Community theaters, churches, and union halls became places where working people gathered not just for aid—but for meaning. Barter networks, cooperative kitchens, and self-help organizations proliferated.

The Rural Crisis Deepens

1930 was a particularly brutal year for rural America, and the damage would take a generation to repair.

Farm foreclosures surged. Sheriff’s sales became public spectacles, often protested or disrupted by neighbors forming “penny auctions”—where they would drive off other bidders and buy the farm back for the family at a nominal sum.

Despite this resistance, the collapse of rural credit structures—like community banks and farm cooperatives—meant that many farmers would never recover.

In the South, African American sharecroppers were especially hard hit. Already trapped in cycles of debt, the economic downturn wiped out any hope of escape. Racial inequality compounded the suffering.

Public Opinion Shifts

By the end of 1930, the patience of the American public was wearing thin.

The image of Herbert Hoover as a competent technocrat had eroded into that of a cold and distant executive. His frequent optimism—declaring the crisis was "almost over"—rang hollow to the unemployed and homeless.

In December, polls and editorials began to reflect growing unrest. While some remained loyal to the Republican Party, many working-class voters began considering alternatives—setting the stage for the Democratic sweep in 1932.

“1930 didn’t just deepen the economic depression—it marked the beginning of a political realignment,” Dr. Markov argues. “A new consensus would eventually emerge: that the federal government must take a more active role in economic life.”

Toward a New Deal?

Though Roosevelt wouldn’t take office until 1933, the seeds of his New Deal philosophy were already being sown by the failures of 1930. Local leaders began experimenting with public relief programs. Academics and advisors—many from the Progressive tradition—started to imagine new models for federal intervention, including jobs programs, insurance, and labor protections.

Ironically, the Hoover administration helped lay the groundwork for these reforms by proving what didn't work. The voluntary, business-led approach faltered in the face of systemic failure.

“1930 was a sobering lesson in limits,” Briggs concludes. “Limits of markets. Limits of voluntarism. And the limits of public patience.”

The Descent, One Year Later

By the final weeks of 1930, the optimism of early spring had vanished. The stock market was again in free fall. Commodity prices remained depressed. Over four million Americans were out of work. An invisible curtain had fallen across the country—not of iron, but of scarcity and silence.

The Great Depression was no longer just a financial event or a farmer’s plight. It had become a national reality. And as the decade would reveal, 1930 was only the beginning.

As Dr. Markov puts it: “If 1929 was the lightning strike, 1930 was the year the fire spread. And America, for the first time in its modern history, didn’t know how to put it out.”